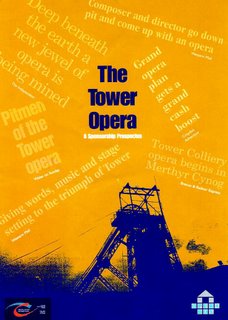

Tower/ Opera

TOWER : The Opera

The world premiere of the new 'Tower' Opera will

take place at the Grand Theatre, Swansea, on

Saturday 23rd October and 100 tickets at 1

pound each have been reserved for a limited

period only, for families of mineworkers at Tower.

The opera follows the dramatic events which led

up to the buy-out of the pit, and stars international

bass, Robert Lloyd, and soprano, Bridget Gill,

along with other leading names from the world of

opera, as the main characters in the story. Even if

you have never seen an opera before, we hope

you will feel justly proud to see the re-enactment

of our achievement on-stage for all to see.

The four performances at the Grand Theatre,

Swansea will run on the 23rd,26th,28th and 30th

of October. Ticket prices range from 10.50 to 25,

with the show touring throughout Wales in

January and February 2000, including The

Coliseum, Aberdare on 15/16 February.

Source here

bbc.co.uk

Tuesday, 18 January, 2000, 12:47 GMT

Curtain falls on Tower opera

(...)

Tower was written by Welsh composer Alun Hoddinott and tells the David and Goliath story of Tower Colliery near Hirwaun in the Cynon Valley.

'Great drama'

The miners made history during a triumphant march back to work in 1995 after using their life savings to buy the pit, saving it from closure.

"This is a marvellous opportunity to create work around real people and real situations," said Mr Hoddinott.

"The story of Tower Colliery is a great drama and its success shows that real heroes can still emerge."

The libretto has been written in both English and Welsh by TV and radio scriptwriter John Owen.

Source here

New opera celebrates colliery's dramatic story

here

Tuesday, September 21, 1999 Published at 08:48 GMT 09:48 UK

UK: Wales

Opera chronicles Tower Colliery survival fight

(...)Director Brendan Wheatley hopes it will bring down the perceived barriers of elitism and bring opera to the masses.

"It's an art form for everyone and by doing an opera about a working class subject and getting it to the people with a huge education programme, which will bring in people, - an a contemporary opera at that, I think it's going to break down a lot of barriers."

More here

fastcompany.com

Underground Activists

From: Issue 52 | November 2001

Back in 1831, Welsh coal miners at the tower colliery invented the red flag as a symbol of rebellion. Today, miners own the mine, and they are focused on black ink and producing lots of it.

Work is personal? No one knows that better than Tyrone O'Sullivan. The toughminded union leader turned entrepreneur wept the day that the British government closed the Tower Colliery -- the last remaining pit in Wales -- seven years ago

"This has never been just a place I've come to work," says O'Sullivan, 56, a veteran of six strikes between 1969 and 1984. "My great grandfather and two of his sons were killed in mining accidents. My father died at Tower when I was 17. I've seen 14 men die within arm's length of me -- more than many soldiers see in battle. But what else could I be but a miner? A cow gives birth to a calf, not a sheep."

So it was an intensely personal battle when O'Sullivan led an improbable employee-buyout effort in 1994, confounding former bosses and turning the condemned pit in Cynon Valley near Hirwaun into a commercial success. The story of the miners' takeover of the Tower Colliery has been celebrated in a Welsh opera, and British movie-production company Working Title Films (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill) has commissioned a script about how the underground rebel with a matinee-idol name inspired his men to one final victory against the odds. "We call him Geronimo," says Brian Loveridge, the gatekeeper at one of the mine's entrances, with a laugh.

Miners here trumpet their legacy of rebellion. The first time a red flag was used as a symbol of revolt occurred at the Tower Colliery in 1831, after a strike at a nearby mine spread to Hirwaun; miners and ironworkers soaked a flag in calf's blood and used it as a battle banner. The story stayed the same for the next 150 years: Low wages, long hours, and dangerous working conditions galvanized miner resistance, which continued long after the industry was nationalized in 1947.

But the most implacable opponent of the miners proved to be the Thatcher government of the 1980s. Pursuing an unrelenting privatization-and-closure program and leaving for dead whole towns built around mine shafts, British Coal shut Tower in 1994, claiming there was no longer a market for anthracite.

The workers didn't believe that, however, suspecting (correctly, as it turned out) that the managers wanted to buy the pit for themselves. And while none of the Tower miners had a degree in geology or an MBA, they knew their mine. Many, like O'Sullivan, had worked at the coal face for more than 30 years.

Within a week of the closing, the workforce had voted unanimously to buy back its pit, and it formed a buyout group, electing O'Sullivan, branch secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), group chairman. Each worker chipped in roughly $12,000 of his redundancy money to rescue the mine -- and with the backing of local banks, coal buyers, and well-wishers, the miners secured nearly $16 million, beating a management-buyout bid. On January 3, 1995, O'Sullivan, a brass band, and 239 face workers, electricians, fitters, shot firers, and engineers -- each one a shareholder in the new cooperative -- marched back to the colliery to take control. Says O'Sullivan: "We were ordinary men. We wanted jobs. We bought a pit."

(...)

How do such achievements fit with the early part of his résumé? O'Sullivan sees a natural progression. The NUM of the 1960s was Britain's strongest, most influential militant union, but offered the trained electrician a parallel career path.

"In British Coal, there was no leadership. Managers simply followed the dictate of the government," O'Sullivan says. "But when I joined the union in the 1960s, miners were the thought leaders at the vanguard of improvements for working people and society. Mining destroys your lungs, crushes your body.

"Working underground makes you crave improvement. A century before, it was the miners' dues that helped build institutes of learning, theaters, libraries, reading rooms.

"Our job in the union was not only to represent our workers," he says, "but also to explain to them what it meant to work together, share together, support the national health service, improve the education system. The world was what we were working with."

Source here

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home